Bambino is a story about people and a place, or rather places. One of them is the Bambino snack bar, where the four main characters meet. Another is the whole of Szczecin and the surrounding area, a city that has been badly churned up by history, to which people from various parts of Poland made their way after the war. We follow the fortunes of the four heroes from before the war up to 1980.

Iwasiów sketches the life stories of actual people, which are firmly set in their socio-historical background, but which also come together to form a single model of human fate: that of people who are crippled, battling in vain with the traumas and painful memories of the past which ultimately cause all of them to suffer defeat, miss their opportunities in life and feel unfulfilled, or simply unhappy. Bambino is first and foremost about the painful consequences of being uprooted and having one’s identity shaken. It is a sort of family-and-city saga that gives the reader a better understanding of Poland and the Poles, and also of themselves.

– Robert Ostaszewski.

Excerpt, translated by Antonia Lloyd- Jones:

MARIA, BORN 1940

Maria carries it inside her, I swear. An image of the journey, but not only. Something that happened in the course of it. Something left far behind her. Like all the others, she has this something inside her, the threads run together, the genes, they intersect, various things can arise from this combination, and I want to find out who they are – perhaps it is actually my story, but it could just as well be not mine or anyone else’s. I want to rummage in the pictures, carbon copies and waste paper. There’s nothing to hold on to, no album, no diary, no central concept, apart from need. There are just disconnected stories instead, whatever someone has made up about himself. About the person he is. And a life, quite simply, his or whoever’s, past and continuing. That’s all we have on the subject. Centrifugal motion, stealing up from behind, the same thing but with no prospect of the same thing. The mother of all such lost illusions – that’s Maria.

I’m starting with Maria, because her name attracts me. All women are called EveMaria. This one all the more so, as if she were made out of her name straight off from the start, more than Eve, naturally, less marked out, or chosen from the crowd, but then no one ever promised her that. No one did, in naming the girl, yet that’s just what she longs for, to be designated. Thoughtlessly giving a girl that name is a way of tempting and inviting fate. It means she is marked out for sure, but let us not forget that Maria is a common name in this situation. It is sure to be the name of every third heroine whose life began in the circumstances that interest me, the ones I regard as a part of the image of the journey. Quite simply, our grannies often had that name. I’ve got nothing to be proud of, because we’ll see what happens to those names and to them further on. They were only brought here in 1957. They were brought here. They were brought by train, but first someone gave permission, issued documents and stamped their decision on them. First came their and those people’s hesitation, the decision was just about to be made, but then the hand was withdrawn, the circle turned, and they went on standing by the same fence. Until that final moment. And it wasn’t at all funny or heroic in those – of course, nowadays we say “cattle” trucks.

But everyone travelled in them – what could they expect? It was still just after the war. All the transport had been used up, the saloon cars had been used for something else, to transport important people who took important decisions, even the fourth-class carriages, carriages of every class. So what did the people and all their things end up packing into? And what sort of – who, where – cattle did it carry? What did “cattle” mean at the time when those railway trucks left German, usually German factories? Russian, Soviet factories worked to a different track gauge, and thus a different axle size, which could, which did serve many sentimental, symbolic arguments. Thus emphasising, repeating the fact that they travelled in cattle… Each one of them, each woman and each man, once travelled on some sort of train to a city, then further on, to a bigger city. If we compare what else “cattle” starts to mean. They too had taken their decision, a decision that could not be regarded as fully independent. In fact it can’t really be called a decision. Yes, that should be the starting point – it can’t be called a decision. The decision starts later on, it can be added onto events. They burn your house down, they come and take your crops again, and there aren’t even any potatoes; nor has there been work for a long time, no work as such (maybe there never actually was work as such; yes indeed, at one time there was even work as a sign of the fact that you exist); the kitchen garden’s been torn up to the last cucumber, at school the children are being taught to forget their own language (at least that’s what’s being said, because no one’s really sure they’re not teaching them the language, which is another delicate matter, the right language for the future); the neighbour opposite must have said something to her NKVD lover – she’s got a grudge about some old stuff, some slander perhaps, and the neighbour on the left keeps saying louder and louder that it’s strange. Maybe she resents their youth – they come home from dances, but she’s not with the guy she fancied. Whereas that girl… of course she’s with the guy she fancied… The usual issues, whether village or suburban, everyone’s familiar with them, everyone experiences them, though they soon have no idea what they’re about, they only mean something from a suitable distance.

The fact that they weren’t taken east is strange. The fact that they weren’t taken away from here is strange. The fact that they don’t know what they want is strange. The fact that they’re just sitting here is strange. The fact that… No one knows best what’s better. What language to use. For what reason they should be taken away. If only someone would take a liking to their farm. Reasons are always for some reason. So for years they’ve been waiting for a decision, and they have to decide for themselves who they’re more like. Which grandfather to hide, and which to put on show. Which grandfather could provide an alibi, or prove valuable.

Although both of them, and going back, the great-grandfathers, branching off into the almost mythical past – and let’s mention the mythical great-great grandmothers too; they always knew how to borrow, flour or language – in other words it’s the grandparents who usually prove to be decisive, the bedrock of the ages examined in retrospect, even when they are legendarily silent, because in silence there should have been thought, but in fact there was plain autism, basic, the most basic stupidity, every few generations, or in side lines interlaced with a talent for telling stories, which like a bad gene make for worse survival, because someone who talks can condemn himself. For the memory of sons and grandsons, these autistic and these eloquent grandparents are inarguably the most important, and for the daughters Daddy is… well, well! What a guy he was. We don’t know why, or what exactly Daddy did, we just accept this knowledge from past generations – who the father was and who the mother was. And so do they, the past, not especially cherished in a rural or suburban area, suddenly brought into the light of day. We learn language from our mothers, but what could they tell us in those cottages with the low ceilings and the souvenir print of the Virgin Mary of somewhere-or-other? What could they have said? I’d rather not hear those tales.

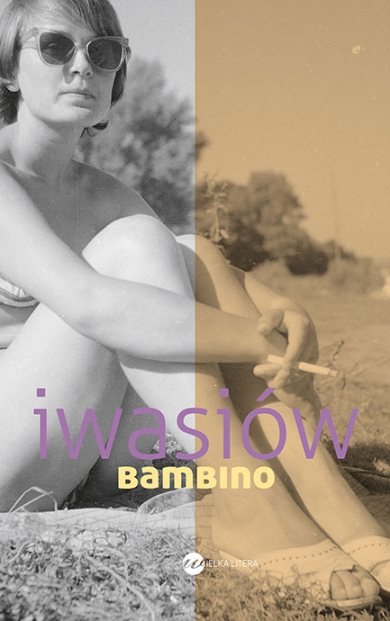

A faded photo of great-grandmother with great-grandfather, stiff poses, and there in the background, in yellow-stained sepia, we can see the poverty. Through the yellow-stained sepia the poverty, or rather the mouldiness of that neighbourhood covered in lush greenery, is even more visible. The mouldiness of this life. The poverty of the neighbourhood and the people, their charm undoubtedly belongs to the past, as they pose for the photograph, but we should assume it may always have been doubtful. Because of poverty, which adds nothing good to figures or features. Charm might show in the children, and so people often say: ‘Just like Daddy’, or ‘That’s Mummy when she was young’. But in the basic issue there is nothing to hide, there is nothing to say about tradition. Apart from the tradition of a bowl of porridge.